Part 1 of Inside Aut Series by Nanny Aut

I spend a lot of time on Facebook and support sites, where autistics try to explain situations from the autistic perspective, in order to help parents understand their autistic children better. One of the most common misunderstandings I come across is processing. Many neurotypicals (NTs) assume that an autistic child takes in and processes information in the same (or at least nearly the same) way that they do. So they are confused when an autistic child has a meltdown over a simple request or a tiny change of plan or when they are asked to stop doing what they are doing and switch to something else. For the NT adult, it is no big deal, so why should it be a big deal for the child?

So, here’s an article that I hope shows why these things are a big deal and some ways that might help in supporting us in the way that we process. Remember the degree to which we experience these differences can vary. For instance, some of us think in patterns and shapes and so may also have the translation barrier to deal with. Some of us have better motor skills than others and so may not need to use as much processing to access speech or hand gestures. There is also a massive range of processing capacity in autistics, not just as a group but within the individual. That capacity fluctuates day by day depending on what’s going on. The more challenging the environment, the lower the spare capacity.

There is a massive range of processing capacity in autistics, not just as a group but within the individual. That capacity fluctuates day by day depending on what’s going on. The more challenging the environment, the lower the spare capacity.

There are several important differences between an autistic brain and an NT brain that affects processing from what we take in, how we process it and how we act on the input.

1. Our core focus and function is to keep ourselves safe. Our lizard brain (or as I call it, Dino brain, because lizards just can’t cause that level of chaos and destruction) strongly believes that sabretooth tigers are still roaming the Earth and if it lets its guard down for one second, we are tiger lunch meat. So not only is it overly responsive, it is actively taking in and processing information from the surroundings with no filter. NT brains tend to assume that we are the apex predator and unless there is repeated evidence to the contrary that there is zero need for vigilance. Dino brain has a good friend, Panic Monkey, whose job is to keep an eye on what is going on and to alert Dino brain if it thinks there is a threat.

Our Dino brain believes sabretooth tigers still exist and letting down our guard means we are tiger lunch meat.

2. Unless we choose activities that specifically shut this off, we take in and process somewhere in the region of ten times the amount of background input that NTs do. NTs have a natural filter in their brains that ignore anything other than the top seven or so pieces of input. For us, we could be operating upward of seventy pieces that we need to ‘manually’ evaluate and identify the important from the unimportant.

For me it feels like I have an air-traffic controller in my head, who in addition to managing day to day operations, manages the input screens, watching and listening, turning volume up and volume down. And these screens take most of his time so he does not have as much available for other processing functions, including keeping Panic Monkey and Dino brain calm and relaxed.

If there is something specific that the air-traffic controller wants to focus on and have processing available for, then they will manually shut down channels through getting the body to fidget or doodle. These are basically automatic activities that take minimum processing and closes most of the background screens. If my eyes are closed and I am moving, this is how I listen and focus best.

We take in and process somewhere in the region of ten times the amount of background input that NTs do.

To focus effectively our brain needs to MANUALLY shut down the extra channels through activities such as fidgeting.

3. In addition to managing and evaluating input, our air-traffic controller also has to manage our sensory signals. Unlike NT nervous systems whose senses run around the middle, autistic senses tend to run too high or too low. This is not just for autistics, many neurodivergent (ND) brains experience this phenomenon. Where these highs and lows are, are very much dependent on the individual, and how extreme these highs and lows are depends on a lot of factors, often environmental. This sensory profile will be discussed in a later post. For now, the important thing to be aware of is that the air-traffic controller is working hard to keep these senses balanced and to identify unlabelled low signals and trying to reduce the ‘volume’ on high signals.

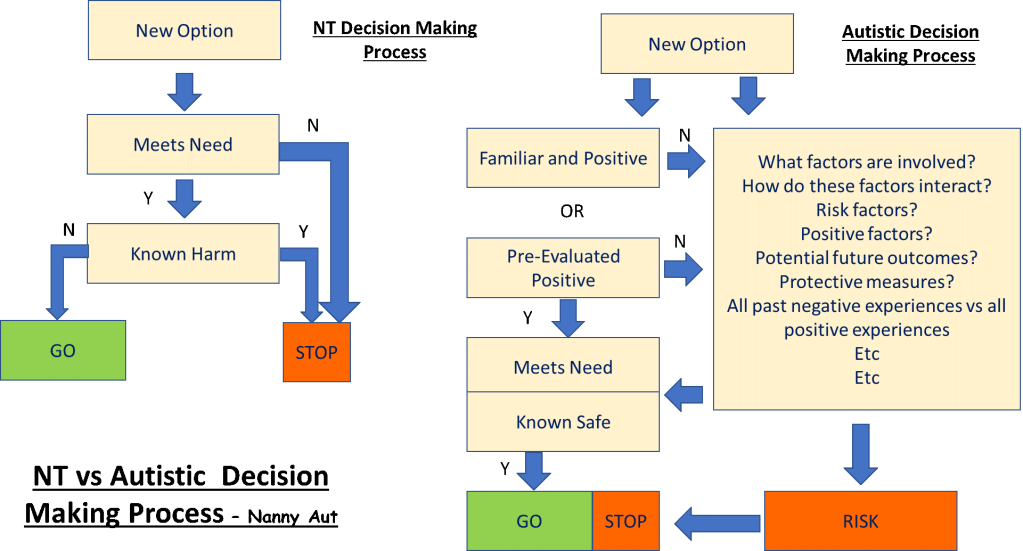

4. As you can see, we do not have the same processing bandwidth available for change. Partly because a lot is already occupied with dealing with input and sensory. Partly because our Dino brain assumes every new decision may kill us, and so needs to evaluate all possible potential outcomes to be certain none of them end with the tiger’s teeth. That takes a lot of processing and we are often not given sufficient time to do it. Particularly if there is a lot of other input going on.

Dealing with change takes a lot of processing and we are often not given sufficient time to do it.

When a new direction comes in, the air-traffic controller has to pull up all available data from past matching patterns and ‘run the routes’ based on previous experiences. Only when it clears as safe, will it get the green light. If the direction is forced before the green light is given, then Panic Monkey steps in. Panic Monkey insists that this route is stopped or we might die. If it is stopped, Panic Monkey can calm down and the air-traffic controller can get back to his job. This is an overwhelm, although it is often misinterpreted as a ‘tantrum’.

Overwhelms are often misinterpreted as ‘tantrums’. If an overwhelm escalates to full meltdown, Dino brain takes over – the air-traffic controller is locked out.

If not, then Panic Monkey wakes up Dino brain, alerting to potential threat. Dino brain then takes over the situation in order to protect us. While Dino brain is in charge, the air-traffic controller is locked out of the controls. This is full meltdown – an autonomic protective mechanism which can present as Fight, Flight, Fawn, Flop or Freeze. These will be discussed in a later post. During a meltdown presentation varies widely depending on the protective mechanism chosen. Most well known is the fight presentation – hitting out, shouting abuse etc. or flight – where we try to bolt to escape the situation. Sometimes you will also see self-harm behaviour as we try to use a pain focal point to anchor ourselves in the mental hurricane.

5. This lack of spare processing bandwidth also affects our ability to transition. Because of processing capacity limits, our brains like to focus on doing one thing at a time. When we need to leave that activity, we need ample warning and a clear ‘close’ point. Think saving and closing on an App. If we can’t complete, then that App stays open and keeps trying to run, even though it is completely incompatible with the new App. This can cause the whole system to crash. The whole board shuts down, triggering an Emergency Alert and Dino brain takes over.

6. Lack of spare processing bandwidth means we can also overload easily. Too much processing too fast such as multiple or open-ended questions requiring and immediate answer. Too much or too complex input, such as live singing or a supermarket. Not enough time to take in, evaluate and formulate a response.

Lack of spare processing bandwidth means we can overload easily.

A very common open-ended question that can push autistic children into overwhelm or meltdown after an exhausting school day is ‘How was your day?’. Our brains spin trying to identify exactly what the questioner is looking for – a quality statement – good, bad, ok; a blow by blow description of the whole day; highlights – and if so which highlights; a basic ‘Fine’ because they don’t really want to know; will my account upset them; make them disappointed in me; can I actually remember anything that happened today? And so on. Best to not ask at all until we have had time to get home, rest and decompress and free up some bandwidth. And when you ask, be specific ‘Did you enjoy break today?’ ‘What did you learn in Maths?’ ‘How did you get on with Fred today?’

7. Finally, lack of processing bandwidth can disrupt or mangle what we take in. For instance, three instructions given one after the other. The air-traffic controller takes in the first one, starts to process it. Then another instruction comes in. There is only process room for one, so the first instruction is deleted, in order to process the second, and so on. What is processed moves forward, so we may not be aware that we have not picked up the whole thing. This is also why we often experience processing ‘lag’, where our ears hear the words, but we don’t actually know what is said for a second because it is delayed in processing. This often means that we ask someone to repeat, then say ‘Don’t bother’ because the message has finally arrived.

Lack of processing bandwidth can disrupt or mangle what we take in.

Knowing why processing affects how we interact with the world is only half the challenge, knowing what to do about it is the other half. These are solutions that have worked for me and for other autistics I know. This gives them a high chance of working for other autistics, but no guarantee, we are all individuals.

1. Have a focus on ways to keep us feeling safe. A safe place to retreat to. Freedom to exit if beginning to overwhelm. Sensory objects that trigger a sense of security. Autonomy and control so we know we can protect ourselves if feeling under threat.

2. Reduce external input. Noise-cancelling headphones/ear plugs, uncluttered spaces, less people = less random interactions, allowing stimming and other focusing activities etc. Account for all senses not just hearing.

3. Find out our sensory profile and work with us to help balance these senses. Reducing input on the high senses and increasing feedback through stimming on the low senses.

4. Plan ahead. Don’t change plans on us last minute. When we are calm and regulated give us the options to evaluate and let us decide what will be the safe alternate routes. For instance, your child may regularly ask for a biscuit just before dinner. They need energy input so you need to think of solutions that provide the same energy input without the boom and bust effect that sugar has. Then after they have just eaten, discuss the biscuits. Explain that biscuits aren’t the best choice before dinner because then you don’t get the energy you need to run properly. So you are always going to say no to a biscuit before dinner – this closes the expectation and sets up the track for re-routing.

Then offer alternatives based on their preferred food choices and let them pick one. Give them time to think about it. Once they have chosen then explain the new route. Next time, if you are hungry before dinner, ask for x. If you forget, I can remind you that this is what you chose.

5. Give us plenty of notice to transition. Timers are often not helpful and can cause anxiety, particularly for those of us with no sense of time. Instead give us a clear close point and a heads-up about the next activity. ‘Finish that round, save up and then we will start getting ready for bed.’ or ‘Three more bounces, then off the trampoline and shake it out. Then we will get ready to go to the park.’

6. Reduce the amount we have to process at one time and give us time to process and respond. Written communication can work really well here – texting instead of speaking, because it gives us the time to read, process and respond.

7. If it is important that we fully understand a message, get us to repeat it back. That way anything ‘lost in translation’ is picked up and identified and misunderstandings are dealt with.

8. The last thing to remember is that processing is affected by external factors – if we are stressed, tired, upset, sick, in pain or in burnout, our processing capacity drops even further. So be aware and adjust your expectations to account for that.

There is a lot more to autistic neurology than differences in processing. There are three fundamental areas that need to be understood to provide effective support. Each of which interwines and interlinks with the others.

Processing

Sensory Profile

Communication and Social Interaction

As this blog progresses, not only will I discuss this support tripod but other elements of the autistic experience that are influenced by these differences.

Hopefully the more that is understood from the way we work the better the support becomes. So welcome to learning from the Inside Aut (yes, I am a sucker for puns and make no apology for that, not even for the bad puns).

Thank you for this! I found it extremely helpful.

LikeLike

I’m an SLP working with autistic children & children with ADHD. Is there somewhere I can find some of the research on this to share with my families? Specifically about the autistic brain processing so much more background input? I think this info can be really helpful as we figure out the best way to help my ND students. Thanks!

LikeLike

A large amount of this is based on my own lived experience and first hand accounts of other autistics during my four years of informal deep dive research (based on Grounded Theory) in my quest to find out how my brain works and how to work with it, This research was only intended for personal use originally, so I collated none of the articles I read. Once I had the information, that was all I needed. However, when I shared my findings with others, I found over and over and over again that what had helped me, helped others too. This then led to me putting my findings into a readable format to help both autistics starting on their journey of discovery, and parents and professionals trying to understand the autistics in their care. The articles from my blog are all shareable and I would be very happy for you to share them with your families, so articles like this one can help them in the same way they have helped a lot of others.

Unfortunately academia is only just catching up to the fact that if you want to know what the autistic experience is, you ask an autistic. This means authentic, autistic research is pretty scarce and even now participatory research is yet to become the gold standard. Resulting in a vast body of very poor quality research based on second hand observer reports and heavily coloured by NT bias and assumption.

If you are searching for good quality academic articles that incorporate the autistic voice then Aucademy – https://aucademy.co.uk/ and Neuroclastic – https://neuroclastic.com/ are good places to start.

I don’t know if you are already a member or not, but I also highly recommend The Therapist Neurodiversity Collective which is a group specifically for SLPs looking to undrstand and support ND clients – https://www.facebook.com/NeurodiversityCollective.

LikeLike

I have read so many books in the quest to better understand my son, and your article is the best explanation I have seen anywhere. I feel like this filled in the gaps on some important ways that I have been misunderstanding how best to communicate with him. Thank you so very much for taking the time to put this together.

LikeLiked by 1 person