Part 2 – Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Mindfulness

by Claire Browne

Monotropism – an affirming way to explain autistic and ADHD cognition. It is an autistic

derived theory initially proposed by researchers Dinah Murray and Wenn Lawson in the early

1990’s. We as autistic people have an interest based nervous system focusing on a single or

a few attention tunnels (as opposed to multiple) leading to very immersive experiences.

Polytropism – a way of thinking where non autistic people/non ADHD people can switch their

attention between multiple sources of stimuli or interests at any given time.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy – a common therapy that helps someone understand how

their thoughts and feelings affect their behaviour. According to the NHS, ‘Cognitive

behavioural therapy (CBT) is a type of talking therapy where a therapist helps you to change

how you think and act.’

Mindfulness – According to the NHS ‘mindfulness involves paying attention to what is going

on inside and outside ourselves, moment by moment.’

Alexithymia – differences/difficulty with identifying and describing own emotions

For those of you who had not read Part 1, this blog aims to explore being monotropic and its implications for mental health as autistic people. Previously I discussed how dedicated interests are central to autistic lives and the connection between alexithymia and monotropism. In this part I aim to consider how being monotropic affects the use and benefit of the common mental health supports Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Mindfulness.

I have had CBT for anxiety and it’s important to note that at the time I was not openly autistic, nor did I have the level of self-understanding that I have now. Despite this, on reflection I can see quite clearly that there were many aspects of CBT that were unhelpful for me. Before I begin to explore the reasons for this in more depth, I just want to acknowledge that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy can be helpful for some people. This blog post just aims to analyse why CBT may not suit autistic people if there is no awareness or understanding of the implications of being monotropic.

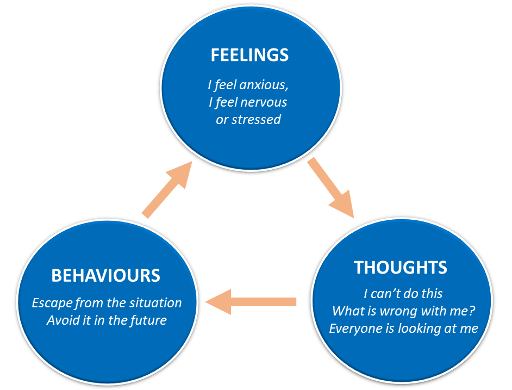

CBT is based on a simple understanding that the way you think will affect how you feel and this will consequently influence your behaviour. Below is a diagram which depicts the cycle using the example of anxiety (the feelings section also includes physical sensations):

Image from Open Learn CBT Module

This graphic shows that the ideas behind CBT are surface level, however as an autistic person I have always known that in order to be engaged in anything I need depth (even though at the time I didn’t have the language of monotropism). As discussed in Part 1, being monotropic means our interests pull us in more strongly as autistic people and that losing an interest can have significant consequences for our mental health. With this knowledge of monotropism, I know that my mood and sense of purpose is heavily dependent on an active interest. What does this mean in the context of CBT? Well, it is really crucial for anyone supporting an autistic person including a CBT therapist; to understand how dedicated interests are integral to daily life. Losing a dedicated interest may lead to low mood or loss of purpose but low mood doesn’t necessarily mean they need to change their thought patterns. Instead they may need help finding another hook for their monotropic brain.

As mentioned in my opening paragraphs, I was not openly autistic at the time I had CBT, and I definitely didn’t understand myself as well as I do now. Even so, I remember being shown lists and examples of unhelpful thoughts that did not make sense to me. These examples of unhelpful thoughts are basically types of negative thinking that CBT aims to change and can include: catastrophising, emotional reasoning, overgeneralising and many more. The ones that stood out to me the most because I couldn’t relate to them were catastrophising and emotional reasoning.

Catastrophising can be defined as assuming or predicting the worst-case scenario in a situation.

I can see how recognising this type of thinking may be helpful for some people, however for me as a monotropic autistic person, my entire reality is intense and therefore the way I experience the world can be misconstrued. This intensity that comes with being monotropic needs to be understood as it can easily be misinterpreted as catastrophising amongst many other things. For example, in part 1 I describe the potential impact of losing dedicated interests and the lack of purpose that may accompany it. For an autistic person, whose life revolves around passions, losing them (or fear of losing them) may feel catastrophic. This is not a thought pattern that needs fixing, but instead a reason to understand monotropic autistic neurology.

As discussed in part 1, being monotropic means we as autistic people focus intently on one or a few attentions tunnels at any one time leading to very immersive experiences. This influences how we experience emotions as our sole focus may be on the current moment. We may have big feelings as a result and it’s important to recognise that just because our emotions are intense (particularly if they are negative) it doesn’t necessarily mean we are catastrophising. Feeling deeply (especially if noticeable to other people) is often something that is shamed, discouraged or pathologised by wider society, however neurokin your sensitivity and depth deserve to be validated and valued.

Aside from catastrophising, emotional reasoning is another type of unhelpful thinking habit that was discussed in my CBT sessions.

Emotional reasoning can be described as assuming that your thoughts or feelings reflect reality.

For example ‘I feel anxious so I must be in danger.’ I can understand how learning about emotional reasoning can be useful, after all not every thought we have requires immediate action or is a cause for concern. Despite this, being monotropic means that when I am in an attention tunnel, the thought or task I am focusing on feels extremely urgent. I cannot switch my attention to something new until I have acted on whatever is consuming my thoughts. Therefore, if I feel anxious, I may not be able to easily reassure myself that I am not in danger. Furthermore many autistic people experience alexithymia, this feeling of disconnect from one’s own emotions could make trusting thoughts and feelings very difficult. On reflection, I can see quite clearly why these unhelpful thinking habits made no sense to me as an autistic person, it just highlights why understanding monotropism and alexithymia is so important.

Another aspect of my CBT sessions that I can remember quite vividly is the worry box.

Now, the idea of the worry box is that you fill a box with a list of worries and dedicate a specific time of day to talking about them. If you feel the need to talk about whatever you are worried about earlier than planned, you are encouraged to try and wait until the agreed time. I also recall being advised to put a limit on the number of anxieties I talked about during my dedicated ‘worry time.’ I completely understand the intentions behind this idea, no one wants to be thinking about their anxieties all day. Nevertheless, deflecting my attention away from what has caught it, is impossible as an a monotropic person. As mentioned above being monotropic creates a sense of urgency that cannot be ignored or postponed. Focusing intently on one thing is all consuming, this is heightened if I am anxious about something as my brain cannot just let it go or be easily distracted. I may instead perceive immediate threat.

The concept of a worry box may be helpful for a polytropic person, they may be reassured that they are not ignoring their anxieties but instead allocating time for them. A polytropic person may be able to switch their attention away from their anxiety and distract themselves with hobbies or other tasks during the day. In contrast, for me as a monotropic autistic person using a worry box is actually quite stressful and therefore counterproductive. Neurokin, if this part of CBT is not helpful for you, it’s not a personal flaw but instead your monotropic brain working in its most natural way. It’s really important for anyone supporting an autistic person including CBT therapists to understand that concepts like the worry box may actively oppose our natural cognition. Understanding monotropic neurology means acknowledging that we can’t choose what hooks our attention (an interest can be anything that we focus on), but when our attention is caught, we are in deep.

Mindfulness can also be incorporated into CBT sessions too, and according to the NHS is defined as ‘paying attention to what is going on inside and outside ourselves, moment by moment.’ I have never found general mindfulness approaches helpful.

In my experience there has been a lot of emphasis on clearing your mind of thoughts and whilst I understand the purpose of this and the benefits of slowing down, my monotropic mind is rarely quiet. Being monotropic means I am always looking for an attention tunnel or alternatively full of ideas for my next blog at the most inconvenient of times.

If mindfulness is truly about living in the present moment, then aren’t there other ways we could achieve this as autistic people that already come naturally to us? The most obvious of which are flow states, the deep immersion that our monotropic brain craves is a prime example of living in the here and now. Accessing flow states requires ample time and the feeling of safety that comes from knowing you will not be interrupted. This is hard to come by in predominantly polytropic environments, but neurokin understanding and embracing being autistic means making time and space for what’s important to you – including prioritising passions and monotropic flow! A recurring theme throughout Part 1 was that dedicated interests are integral for our mental health as autistic people, and it’s important to note that flow states can both give and drain energy. The thrill of feeling so in sync that the outside world fails to exist, coupled with the realisation that basic needs are not met is one of the many implications of being monotropic and is difficult to balance. However this intensity of monotropic flow can provide the same sense of presence that other mindfulness approaches aim to create.

Another way we as autistic people may be able to immerse ourselves in the current moment, is by celebrating autistic joy or more specifically sensory joy. Feelings of elation or deep satisfaction stemming from eating your favourite same food , stimming freely, or appreciating the intricate details on a leaf falling from a tree may be helpful to seek out regularly. Stimming is a big part of autistic culture and is an intuitive way to express all emotions. If typical mindfulness approaches are not helpful for you, then mindful stimming may be an alternative. According to Aucademy’s ‘Autistic Sensory, Stimming and Relaxation techniques video mindful stimming is ‘just stimming and paying attention to the object you are looking at, because you are interested in it.’ Mindful stimming is really appreciating your stims, whether that be the texture of your treasured stim object or (alternatively if you can’t use stim tools) each individual note of your favourite same song. This may already come naturally to you, as autistic monotropic people anything that captures our interest is likely to be all consuming and stimming is no different. I suppose the reason for describing this aspect of our culture as mindful is to emphasise the alternatives to mindfulness that could work for us, not against us like many approaches do. Equally for those of you who are not able to stim freely, setting aside a specific time for mindful stimming may be helpful, an opportunity to explore your autistic identity more broadly.

Though this blog has primarily focused on CBT and mindfulness as formal mental health supports, the most powerful, beneficial form of help for me has been completely understanding and embracing being autistic and the sense of belonging that comes with being a member of online community spaces. Everyone deserves to know who they are and learning about monotropism is key to making sense of and crucially affirming autistic experiences whether that be for us as individuals or for those that are supporting us.

On that note, I hope that this blog series emphasises the relationship between being monotropic and autistic mental health, the significance of self-understanding and ultimately the importance of finding mental health supports that work with our monotropic neurology, not against it.

References: