Image by Džoko Stach from Pixabay

By Nanny Aut

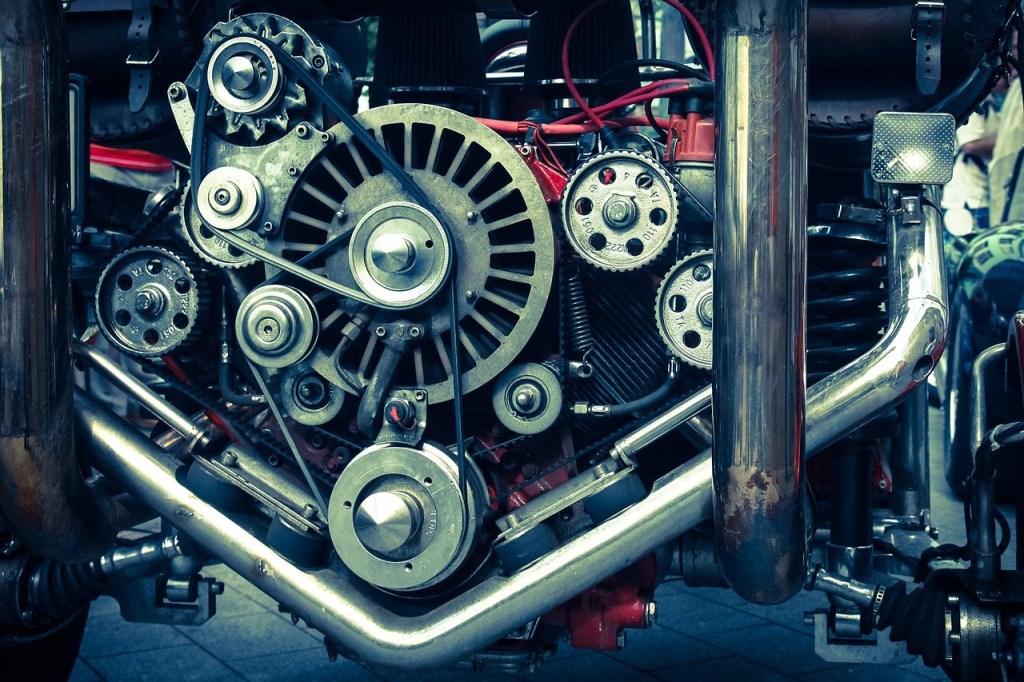

I am – at core – an engineer. This means I like to take things apart, examine the components and figure out how everything works.

And the key lesson I’ve learnt is that machine components interact with each other. If you have a failing component – there is every possibility that you need to look further than the component. What is interacting with that component to cause it to fail?

And the same is true for humans too. We are interconnected. Our experience is based on action and response.

However, when it comes to research on autism – this fact often seems to be forgotten. Either every component is lumped together as one machine – ‘It’s all autism’ or each component is treated as a standalone item.

Sensory Issues.

Social Challenges.

Repetitive Behaviour.

Etc.

In doing my research and in listening to autistics talk about their experience, I noticed that there seems to be four key components at play. And how they interact with each other determines our capacity to cope with our environment.

Processing, Sensory, Energy and Safety.

Processing

This is one of the core differences between autistic brains and the majority brain.

Research has shown that, not only do autistic brains develop more connections per neuron during brain development pre-birth, we also prune out a lot less of these connections as we mature. This means that every time we process something there are a LOT more connections firing than in a majority brain. Sometimes this is a good thing and allows for excellent pattern spotting. Sometimes it’s a bad thing like creating crossed wiring and causing overloads.

Add to this the fact that autistic brains take in a LOT more information than majority brains and you can start to see how much extra processing is happening. Autistics don’t have the 5-9 filter that the majority have. We don’t cap our information and ignore anything over the 7-ish item limit. To our brains EVERYTHING is important until evaluated and shown to be otherwise. This can bring benefits, such as seeing what others miss, and also downsides such as missing what is important or easily overloading. And often a terrible working memory – when your In Tray is constantly overflowing, it’s easy for things to get lost or not get processed until several days after the event.

Decision making also adds to the processing load. Unless we feel really SAFE with a decision, that we know from experience that this choice works well for us, we tend to calculate out every decision, taking in all known data, calculating potential outcomes and evaluating which is the optimal choice.

A simple ‘How was your day?’ can create an overwhelming cascade of decisions.

What information are they looking for? What mood are they in? What can I say that won’t upset them or lead into a long discussion I don’t have the ENERGY for? Etc. Etc. Etc.

Even something that looks obvious like ‘Do you want pizza?’ can trigger a cascade. What pizza, from where, when did I last have pizza, what is their delivery time, can I rely on this pizza being identical to last time? And so on.

This is something I greatly envy the majority about. For them the default is a simple ‘Yes/No’ for the majority of decisions. Their brain trusts that it can automatically select the right decision. The detailed decision making that autistics tend to do for every decision is reserved only for key decisions (and sometimes, it seems, not even then).

As I said before, nothing is a stand-alone component.

The spikier our sensory profile is – the harder our processing has to work in order to bring things to a more even profile.

Processing takes a lot of energy – so the lower our energy supplies are, the less able we are to manage processing demand – to the point our processing can cease to function.

The more we feel unsafe – the more active our limbic system becomes and the more our processing needs to manage that.

Sensory

I cover the sensory aspect of the autistic experience in two of my earlier blogs – Making Sense of the Senses – Part One and Part Two.

So I will keep it brief here.

A common aspect of the autistic sensory system is the spiky sensory profile. Some senses are amped way up and some seem to be a weaky-squeaky signal that is hard to notice. We may be more aware of a spike in anxiety when a low sense is sounding the alarm, instead of noticing hunger, or pain, for example.

The more energy we have and the lower the processing demand, the smaller those spikes become, meaning we are less likely to be overwhelmed by our high senses and more likely to pick up our low senses. Our need to stim may also drop if it’s linked to our need to increase sensory signals.

The spikier our sensory profile is, the more unsafe we feel, because our brain knows it isn’t getting an accurate read on our environment. Especially with the ‘missing’ low signals.

And when our brain does pick up an alarm from a low signal – it knows there is a threat – but it doesn’t know where the threat is or how to address it. Which causes anxiety to soar.

Even worse, it’s a vicious cycle – spiky profile – reduces sense of safety – which increases the spikiness of the sensory profile – which puts us more under threat – which increases the spikiness of the profile further – and up and up we go until Dino Brain takes over.

Energy

Like the Sensory Profile, I have already written a blog going into energy demand and supply in depth – Dam, Fork n’ Spoons – Managing the Autistic Energy Supply.

So – straight to how it interconnects.

The higher the processing demands, the faster our brain burns through the energy it needs to function, which can leave autistics feeling exhausted or dealing with burnout. As well as then struggling with brain fog – because the energy is no longer there to process with.

The lower our energy supply is, the more spiky our sensory profile becomes because there is no longer the energy for processing to manage it.

Which can leave us in a Catch-22. We need to eat in order to boost our energy supply – but we can’t eat because all food has become sensorily overwhelming or the flavour, texture, bite complexities of the food is too much for our limited processing capacity. This is why safe foods are so crucial and should never be messed with.

And the more unsafe we feel, not only do we burn through more energy through becoming hyper-alert, we can also opt to stop eating altogether. If we need to be ready to run – now is not the time to eat. Our digestion can shut down completely as blood supply is moved to get us ready to fight or sprint. So we again – get caught into a vicious cycle.

Threat – energy drop – no way to replace energy because of threat – energy drops further – which increases threat – no way to replace energy because of threat – and on we go.

Safety

I have left this one to last – because I feel this is the most important. Get the sense of safety right and everything else works better.

If you want to know more about why our sense of safety is so key then I have an earlier blog Dino Brain and Panic Monkey vs. The Air-Traffic Controller that you can check out.

Suffice it to say that there are a lot of reasons that our limbic system is more active than the majority. Possibly partly genetics – born with a larger limbic system, definitely a lot of trauma living in an environment that doesn’t support our nervous system, definitely a lot of trauma from the isolation and bullying for the ‘crime’ of being different.

For many of us, our experience has taught us that the world is not a safe place – that harm exists everywhere. And that we can’t rely on anyone else to protect us.

Which means our brain is constantly scanning for threat, massively increasing processing demand. This is one reason why we like the familiar, why we love our monotropic tunnels, why routines can help. We know that these scenarios are safe – which means we can drop our guard and lower our processing demand.

Conversely, in new situations or situations where we’ve been under threat or even harmed before, scanning and processing increases. A LOT.

Which increases processing demand and reduces energy, often causing a sharp processing drop as there is no longer capacity nor energy to manage the level of processing demand needed.

Which creates another vicious cycle (are you starting to see why meltdowns can appear to come out of nowhere?) – threat – increases processing demand leading to a processing crash – no longer processing available to scan properly for threat – increasing the sense of danger – stripping processing more – in comes Dino Brain to save the day.

And the more under threat we feel, the spikier our senses become as our brain turns up the volume on senses needed to keep us safe and turns down the volume on senses less related to immediate danger. Which then creates a threat of its own because we’re no longer getting an accurate read on our environment.

Conclusions

To conclude – we need to consider support as a whole not as an individual item. There is no point in sensory accommodations if processing, energy and safety aren’t also considered.

To do well –

We need to feel safe – connected, secure and predictable environment. No threats of punishment, ignoring, or isolation. Assuming we want to do well and showing us how to do that goes a very long way.

We need to be able to reduce processing demand where possible.

We need to be able to manage our sensory profile – reducing input from high senses and increasing input from low senses.

We need to take into account our energy needs and be able to manage them.

All together – it’s not a pick and mix where you choose to prioritise one over another. That’s like choosing to take great care of the chain on your bike but not looking after the gears or the wheels.

One thought on “Why Holistic Understanding Is Important”